America’s Post-2008 Economic Landscape, Understanding the Critical

Difference between Dollars and Votes and a Clarion Call for Action

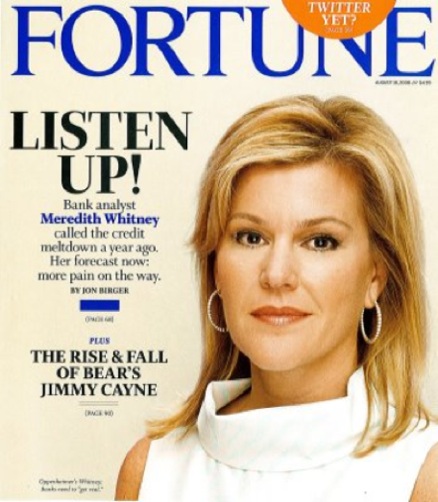

If one is trying to generate buzz in the financial world, perhaps the best way to do so is to involve Meredith Whitney. This intelligent and charismatic analyst, whose controversial call that Citigroup resembled a “house of cards,†made her a star. Deservedly, she became one of the leading pillars of economic commentary who helped alert the public to the rot that prompted 2008’s financial meltdown. With her new book, “Fate of the States,†Whitney has focused her attention on the crucial themes of governmental ineptitude and its impact on the safety and stability of both public and private finance.

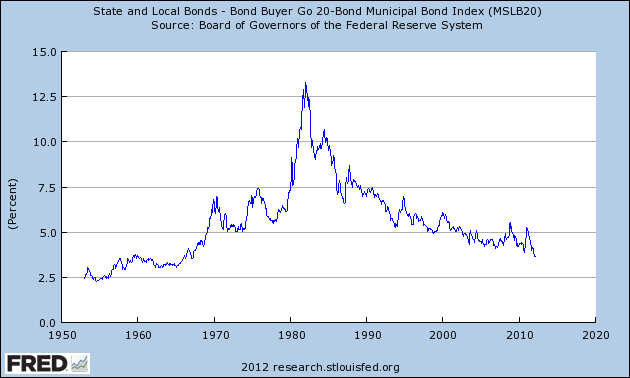

At a time when equities face looming volatility and stunningly low interest rates have already spooked many fixed income investors, without doubt, she has written the right book, for the right audience and at exactly the right time.  In particular, her narrative sounds the alarm about the creditworthiness of what is supposed to be one of the most stable (and widely held) asset classes for investors: municipal bonds. By casting a spotlight on an often misunderstood sector, Whitney convincingly argues that “business as usual,†is already having seriously negative consequences for our national economic and political well-being – consequences that could easily begin to grow exponentially. After all, municipal bonds offer a uniquely powerful lense through which to examine America’s vulnerabilities: on the one hand, their current lack of stability demonstrates a loss of confidence in public institutions and leadership while, on the other, investor skittishness about making these investments can be directly correlated with government’s inability to effectively function.

Throughout, Whitney does an excellent job summarizing (and contextualizing) a host of broad and challenging issues without losing focus.  In essence, Whitney’s thesis is that American government has grown inherently over-leveraged, producing metastasizing effects throughout the public and private sectors. The results include businesses (particularly small and medium-sized businesses) in jeopardy of losing their ability to finance future growth, stubbornly high levels of continued unemployment and state governments increasingly unable to afford the communal services that would normally offset at least some of the damage. Instead, the decreased ability of states and localities to reign in infrastructure deterioration, fund education, or provide other basic services risks creating a “spiraling†effect in which neither government nor business has the resolve or ability to “bail out†its counterpart. For anyone who imagined the big bank collapses and housing crisis of 2008 are as bad as it gets, Whitney’s perspectives offer a significantly more chilling vision of the future.

The book opens by exploring both the evolution and demography of America’s economy in order to set the stage for Whitney’s discussion of the housing debacle, its resultant impact on financial institutions, and a deeper evaluation of the nation’s economic condition. Step-by-step, we are led to her central focus: the shrinking finances of America’s states and municipalities. In doing so, Whitney deftly navigates some demanding terrain and leaves the reader with a thorough understanding of the states’ (and their cities’) precarious financial circumstances.

What she alludes to, but doesn’t spell out, however, is the powerful dissonance of incentives that exist within the public and private sectors. Dollars and votes are two different currencies of success. Private sector performance is measured in profit generated by business. Private sector power comes from generating profit for investors. Disruption, innovation and, to some extent, reliance on (functional) government are what fuel the world of business.

Conversely, public sector performance is measured in votes – a “currency†earned by politicians able to demonstrate effective on-the-job performance or at least create its appearance. Here, power comes from creating or maintaining conditions sufficient that a majority of the people believe – at minimum – that they will be able to provide for their families and offer their children more secure and prosperous lives than their own. The maintenance of a tolerable status quo, implementation of an appropriate and acceptable tax policy and the efforts of the public sector workforce are the basic means through which government and politicians achieve their legitimacy.

When a private citizen then “spends†these two very different currencies (and all of us inescapably live lives with a foot in each sector), what we hope is that that his or her self-interested decisions not only meet their short term needs but also lead to longer term societal health. Whitney’s scenarios certainly don’t paint a positive picture concerning how that process is playing out. In large part, I have to agree. Clearly our institutions (both public and private) have become too deeply rooted to their own short term priorities. More worrisome still is a “credit card culture†in which citizens too frequently forget to be citizens. Our tendency toward short term self-interest leads to a dangerous expansion of structural bloat in which everyone ultimately suffers. Some of these effects are reversible; some not – and, therefore, what have been the traditionally stable financing mechanisms for state and local governments could now aptly be described as “Whitney’s nightmare.â€

One terrific aspect of Whitney’s writing is her frequent use of carefully chosen examples that vividly illustrate her arguments. This book is not meant to be a PhD thesis or legal brief where every counterargument is anticipated. She isn’t delivering a manifesto. Rather, she’s describing a problem that has only recently received widespread attention (and little analysis). Whitney would probably be the first to admit that the use of compelling anecdotes is not the same as relying on macroeconomic data and statistical analysis. Yet her technique is purposeful and effective. It opens up her conclusions for debate by the wonkier among us while ensuring they remain accessible to those less familiar with the machinations of finance and government. The fact that she is so grounded in the world of economic practicality, as opposed to economist “jibber-jabber,†is what makes this an unusually reader-friendly publication in a discipline not normally associated with page-turning prose.

Nonetheless, it’s crucial to remember there is a reason why so many economists seem so bogged down in the details: there are A LOT of details involved… Whitney’s “state arbitrage†section, for example, is one place where I often found myself simultaneously nodding in agreement with the underlying premises but questioning at least several of her case studies. There is some unmentioned nuance here that could have added significant value – although I’ll freely admit personal bias as this is an area where I have had considerable experience on both sides of the proverbial fence. In the governmental sphere, I worked at the New York State Department of Economic Development and handled many projects involving companies in the process of deciding whether to enter or leave the state. In my current profession, I advise clients on how to arrange their affairs in ways that minimize their state tax burden – sometimes by changing their primary residence or by employing various types of trusts, often domiciled outside their home state.

Given that background, I found that several of Whitney’s state arbitrage examples lacked the sort of sophistication that characterizes a majority of her book. She mentions that Google has located a major server hub in a low cost state, but neglects to explain that they have also made a major push into New York City (essentially by purchasing an entire city block). She highlights the fact that Florida’s population has been decreasing – an observation that would seem to contradict her notion that tax rates are THE driving factor behind what she claims are mass defections from higher cost northeastern states. In reality, population shifts are not only exceedingly difficult to measure in the short term (they are caused by diverse economic, social and cultural factors); something missed when any single element (like tax rates) becomes over-emphasized. One of the chief lessons I’ve gleaned both from working in government and in private banking is the incredible complexity that goes into either discovering or effectively regulating arbitrage activities.

That said, most of Whitney’s discussion of income tax rate arbitrage is still salient and well-reasoned. I receive at least three phone calls a week from clients and prospects seeking advice on the topic and Whitney’s views will certainly inform my own. However, for me, the more interesting discussion actually involves state capital gains tax rates. This subject is of primary concern to hedge funders and private equity mavens because their income is taxed (controversially) at considerably lower rates than ordinary income. It should, however, be of concern to ALL AMERICANS. Moreover, as U.S. territories like Puerto Rico begin inserting themselves into the mix (as John Paulson recently investigated), how and why capital flows between competing localities is certain to become less predictable and even more tricky to manage.

Whitney additionally explores the ramifications “job portability.â€Â I would have liked to have seen more color around the impact of “legacy†and the distinction between industrial jobs and intellectual capital professions that are (presumably) less constrained by geography. I was also a little disappointed to see a paucity of information regarding arbitrage activities taking place between the U.S. and foreign countries. Similarly, other unaddressed factors such as skyrocketing student debt, Congressional gridlock and the yolk of small business regulation are certainly measurable costs that suffocate entrepreneurs on an hourly basis and play directly into the concerns Whitney addresses elsewhere. Finally, I could probably write my own book on the waste involved in state led “economic development efforts†and how any government “bet on the future†almost always goes south. Still this is nitpicking on my part – And meant less by way of criticism than in the hope Whitney continues to write.

I was heartened to see Whitney believes there are areas for improvement in state finances and that the picture isn’t entirely bleak. Certainly, her concept that some entities should default holds merit. Those entities that borrow money to pay for operating expenses are merely putting off the inevitable. I agree that just because something has been rock-solid in the past does not guarantee its future stability. Too often, state and municipal government accounting is opaque at best and deceptive at worst.  When the opinion of the capital markets is the only way to evaluate an entity’s financial condition, defaults are necessary.

In my own work, overseeing billions in client assets, it would be inconceivable merely to look at a single factor when offering investment advice. Therefore, if there is only one metric available, my advice to a client is absolute: the investment should not be made. Indeed, I would be thrown out on the street in seconds (and it wouldn’t be Wall Street…) if I were to rely on the simplistic analysis that is almost the norm for municipalities. As Whitney indicates, municipal evaluation can properly be analogized to grade inflation in college. In fact, it’s far worse. There is simply no way that 99.5% of municipalities are operating at a passing rate. Defaults, even controlled defaults, send the message to investors that there’re playing in an accountable market – not Vegas. Sadly, the latter is closer to reality.

I also fully agree with the benefits of consolidation. The city of Mamaroneck, as Whitney points out, does not need three different police forces. However, the difficulty in consolidation is that corrective action carries a high level of political risk, immediate negative impact (e.g., increased unemployment) and a correspondingly delayed payoff. As stressed earlier, the currency of politics is neither profit nor efficiency. Politics is all about voter persuasion and, obviously, consolidation sounds a lot different to bond investors than to voting parents whose children will be experiencing larger class sizes and living in neighborhoods with smaller police and fire departments. It’s not surprising that many politicians want nothing to do with that type of electoral calculus.

Reformation of the state pension process is another area where the law of large numbers has rendered simple fixes virtually moot. I primarily cast blame on the “financial industrial complex†and the supposedly “learned assumptions†that underpin most large-scale investment and stewardship decisions. This is where one can most clearly observe the dangerous intersection between a greedy, well-oiled selling machine and our often economically unsophisticated stewards of public money. Jefferson County, Alabama and Reykjavik, Iceland (different as they may seem), are each stark examples of public money being the patsy at the poker table.

I found Whitney’s book an engaging and informative primer on the darkening storm clouds now hovering over municipal finance – (and, the United States, itself). Again, there are many other issues that could have been more thoroughly addressed including the privatization of state services (do municipalities get the benefit of their bargain?); the intersection between the states and the federal government; and that most constant of human problems, corruption.  Such omissions, some of which are only partial, however, are hardly fatal flaws.

Most pleasing, is that Whitney leaves her readers with the feeling they’ve just received a personalized “briefing session.†She could literally be sitting right across the room. Her coverage of the lasting effects of 2008, the indulgences of the 2000’s, and the causes of today’s municipal bond calamity is a serious wake-up call for anyone who has yet to fully appreciate the structural difficulties facing our nation and the enormous complications with which even the best among our policy-makers and business leaders must contend.

Overall, “Fate of the States†delivers and is well worth your time. I, for one, am greatly looking forward to “Volume 2,†in which I hope Whitney will offer her audience a deeper dive into the numbers and perhaps a slightly “wonkier†level of analysis.