PERKS AND PITFALLS OF THE NEW GILDED AGE – WHEN SOARING TOWERS HAVE INVISIBLE TENANTS

New York City is enjoying a modern real estate renaissance, a gilded age at a time of low interest rates and international capital movement. As an apartment owner and board member of a New York City co-op, this meteoric rise has been truly astounding (and welcome). However, with the ascent of each new building and every marquee sale, there are clouds of fear and uncertainty curbing the enthusiasm of even the City’s truest believers. The source? Secret buyers, unimaginable sums spent on apartments that never see an actual resident (let alone a couch), and financial maneuvers that sometimes appear eerily similar to the tangled knots weaved by the creators of Enron or the 2008 mortgage crisis. Anxiety abounds – but, really, that shouldn’t feel too surprising. This has always been the world capital of media feeding frenzies. Amidst all the competing narratives, however, sober real estate investors still need somewhere to place their faith and dollars. Let’s start with some basics.

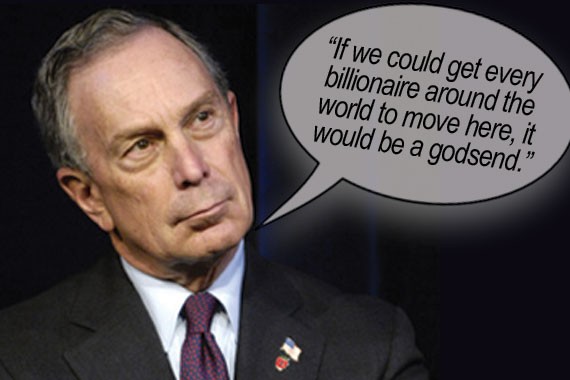

Fact #1: Secrecy can be a valuable currency for outsiders who want to participate in what is a genuine gold rush. Fact #2: Secrecy can easily be abused. This is reflected in a recent series of New York Times articles about the transformation of 57th St. into a so-called “Billionaires’ Row.” Per the above, New Yorkers are a breed apart for whom real estate is a contact sport. In the City that Never Sleeps, the mix of money, status and mystery is as intoxicating as it is traditional. Nevertheless, the evils of money laundering gain more attention by the day. The financial culture of New York’s real estate community accommodates ever more vast and enigmatic wealth. Stealth transactions have swiftly migrated from The Real Estate Section to the Front Page. And while foreign investment has been a part of the City’s fabric well before the construction of the United Nations Building, even some of the most die-hard New Yorkers are feeling ill at ease.

HYPE, A PARADIGM SHIFT OR JUST BUSINESS AS USUAL?

Cloak-and-dagger transactions have been at the forefront of New York City’s consciousness since 2001. Post 9/11, traditional banking havens were choked to ineffectiveness through the slow process of regulation and disclosure. Global bad actors found fewer places to stash their assets. New York City and the world wondered whether terrorism was effectively being financed right in the U.S of A. Stories of shadowy foreign figures buying high-end real estate filled the media. Popular (and governmental) attention intensified as the recent explosion of midtown and downtown luxury residential construction begged the question “Who is buying all of these properties” in an otherwise sluggish economy? Recent Times coverage on the subject comes right on the heels of a New York Magazine article that declared high-end real estate to be the new Swiss bank account.Attorney General Eric Schneiderman has devoted increasing attention to the phenomenon due to his concern that real estate investments could be the latest trend in global money laundering. And neither he nor the investigative journalists are alone.

Mayor de Blasio, joined by a frequently disparate array of advocates for the disadvantaged (or at least disgruntled), bemoan the lack of affordable housing in a City where immense square-footage is suddenly being used as what once was called a “stash“ sometimes going entirely unfurnished. Simultaneously, the merely very rich and upper middle class have raised the specter that even they will soon no longer be able to afford a sufficiently trendy New York zip code. Horror of horrors! (Then again, this too is actually more than a frivolous issue: when apartments are bought but not inhabited, their owners make a much smaller contribution to the City’s economy) And, of course, there is the omnipresent hint of xenophobia: in virtually every published story, it’s impossible to miss the words Russian, Saudi, and Chinese

The implication is that New York City “one way or another“ has some type of REAL real estate problem. Nevertheless, as with most controversies of this nature, things like secrecy, sudden high profile injections of foreign investment and rapidly changing urban landscapes require more than mere surface understanding. There are a wide variety of reasons that real estate buyers might want to shield their identities some valid and some . . . well, not so valid. After all, if a purchaser is motivated to take complicated, expensive, and, perhaps, shady steps to obscure their identity, at least two crucial questions should be contemplated: (1) Are we seeing market forces or illicit activities at work? And (2) is it sometimes not only legitimate, but financially prudent, maybe even necessary, to allow for privacy in real estate dealings?

EXAMINING THE SITUATION FROM MY POSITION AS A CO-OP BOARD MEMBER – THREE KEY POINTS:

I’ve now served on the board of a New York City co-op for the past two years. As you might expect, it can be a challenging juggling act. One person’s annoyance can be another’s calamity. As a board member, I owe a fiduciary duty to ALL the shareholders of my building corporation and that means continuously looking out for the financial health, long-term maintenance and livability of the building. Buyer secrecy, at least in a building like mine, is a deal-breaker for several reasons.

First, concealment adds an unacceptable element of uncertainty and complication when it comes to basic shareholder duties such as the payment of maintenance fees. Secrecy, non-disclosure, or corporate layering all represent serious obstacles to combatting possible fraud or delinquency. Such behaviors pose a clear and present danger to other corporate shareholders one that I can’t, and won’t, abide. Put it this way: I’d worry about my own future investment in any building that has an overly permissive or inattentive board or one that lets in buyers without requisite due diligence. If I didn’t uphold that standard as a board member of my own building, I’d be doubly guilty of shortchanging my neighbors and myself.

I recognize this might seem like hyperbole. IT ISN’T. If a buyer flakes out, flees the country or otherwise refuses to pay his or her fees, tracking down and forcing the wrongdoer to live up to their responsibilities becomes more complicated and costly literally with each passing day. Meanwhile, the rest of the building eventually covers their former neighbor’s costs. If such situations are allowed to accumulate, the overall financial health of the building is threatened. This could have ramifications for the building’s complex web of residents. Serious non-performance by fellow tenants increases assessments, can wipe out value, and, for some, even threaten retirement planning and overall financial health. The result: angry shareholders, lawsuits, and sometimes, a whole lot worse. I have more than enough stress in my life without all that. I’d confidently guess that most others in my position would agree.

Second, it’s my job to make sure that the Board takes all the steps it can to ensure our building remains a secure place to live. I’m just not interested in wondering if my neighbor is an arms dealer or the concubine of a Bolivian drug lord. As a board member sharing a building with multiple owners, all of whom expect me to help preserve their investments and well being, it is never my desire to be a weigh station for miscreants or the unwitting repository of reckless would-be financiers.

Third, a well-managed building is a livable building. The goal of home ownership in New York City is finding a sanctuary from the stresses of urban existence preferably in a neighborhood that meets one’s individual predilections. In a nutshell, that is “the New York City Dream.” Yes, Co-ops absolutely have MANY strings attached both for buyers and sellers. However, these restrictions and board approvals exist to ensure that the building’s citizens (the way I believe board members ought to think about their fellow residents) have a meaningful stake in the success, maintenance, and livability of what is not merely their home, but a home we all share. Shared burdens create shared benefits. Amazingly, some forget that the term co-op is shorthand for the word cooperative. Despite whatever hassles co-op ownership might entail, the chance to enjoy the countless benefits of a mutually reinforcing community is what makes a properly governed co-op successful and desirable. Buyer secrecy nearly always – runs counter to those goals.

BUT WAIT… AREN”T THERE SOMETIMES TOTALLY VALID REASONS FOR CONFIDENTIAL TRANSACTIONS?

Still, as I cautioned earlier, the views I’ve expressed so far have stemmed largely from personal experience. I would never claim that buyer-anonymity is automatically evil nor suggest that all buildings require identical governance. In fact, there are a host of good reasons for real estate anonymity in other contexts. Many buildings’ corporate structures are designed to accommodate realities that don’t exist where I happen to live. In fact, some lucky few buy entire buildings for the primary purpose of maintaining anonymity – something that explains the popularity of townhouses, for example. I mentioned security earlier, both economic and physical, and that’s one issue that unquestionably works in both directions. For the exceedingly wealthy or famous, shrouding both location and balance sheet provides fewer points of contact that a hooligan, terrorist, con-man, or extortionist might exploit (not to mention that I don’t know too many people that would seek out a building besieged by paparazzi- especially if they have children).

Under the right circumstances, I’m also comfortable asserting that certain other anonymous structures, designed to maximize negotiating leverage, have their place. If Warren Buffett wants to buy your house, you are naturally going to use hisfinancial strength as a tool in extracting a better deal. Therefore, it’s equally logical for Warren to want the deal to be an arm’s length transaction so that he won’t end up unfairly overpaying just because of who he is. (Ironically, this dynamic is flipped on its head in LA where famous actors’ homes often extract a so-called “celebrity premium.” Similarly (and within reason), I think it is legitimate to conservatively use anonymity structures to organize real estate holdings to effectuate well-organized administration, long-term tax planning and asset protection. Point being: prudent real estate management is not about absolutes. Or, at least, it isn’t until it is¦

YES – EVEN JUST ONE “FLAWED” APARTMENT CAN ENDANGER YOUR BUILDING!

Where I obviously draw the line is money laundering. It is never right to use real estate secrecy and structural layering to hide the origin of ill-gotten gains. In that regard, I fully sympathize with the New York Attorney General’s concerns. Real estate secrecy is especially difficult to track. It is no overstatement to point out that the pervasiveness of criminal activity in high-end real estate markets (especially New York City) has expanded dramatically. As criminal enterprises go, money laundering remains one of the most expensive and burdensome to investigate. These are neither small nor inconsequential matters.

Consider: How would you feel if a leader of ISIS ended up owning a 5-bedroom apartment in your luxury high-rise (even if he actually lived in a somewhat less pricey cave somewhere in Syria)? Would you worry that perhaps you hadn’t paid sufficient attention? Would you call your co-op or condo board to task? And then, what should we say and do about the facilitators- those all too eager to engineer such transactions? As the Times’ diligent reporters discovered, an entire cottage industry has developed in which unscrupulous brokers, lawyers and other middle-men act as conduits for transactions that range from the questionable to the absolutely illicit. My view: those who pollute the system in this manner should be viewed and treated as the termites they are.

THE UPSHOT: DON’T PANIC! FOR ALMOST EVERYONE, THE NEWS IS STILL GOOD – SO, LET’S REVIEW…

Getting back to basics, where does this leave today’s co-op owners and those considering a dive into the market? Despite what some see as an aura of real estate pessimism (and even fear), as with everything else in New York City, there remains plenty of good news. Governments at all levels are recognizing that real estate secrecy is being used for nefarious purposes. Today, crimes using real property are 100% on the radar and increasingly receiving the intense scrutiny they deserve. Bank regulators have raised “Know Your Customer” standards to the strictest levels in generations. Compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the anti-money laundering provisions in the USA PATRIOT Act have become top priorities for US financial Institutions, federal prosecutors, local authorities and, importantly, a fast-growing number of foreign institutions most of which share some nexus with the US (and hope to continue doing so in the future).

With more sunlight disinfecting dubious transactions, both the government and the private sector, are at last starting to collaborate in ways that substantially raise the costs of being an unprincipled broker, lawyer, or go-between – at least in the United States – and particularly here in New York City. By forcing real estate conduits to legally verify, and publicly account for sources of wealth (or at least sometimes to appropriately do so under the protection of a co-op board NDA or similar agreement), many of today’s secrecy issues can ultimately be ameliorated, if not eliminated. Anonymity and financial structuring techniques will once more become well-intentioned tools for legitimate real estate commerce. Buyers who want to enjoy their pricey views will replace today’s absentees. And, in the ever-proverbial New York Minute, even co-op board members like me won’t feel guilty choosing Page Six over the Real Estate Section when it comes to seeking out scandal and gossip.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: LinkedIn kindly asked me to write this article for their publication, “LinkedIn Pulse”