Among other things, J. Maureen Henderson is a Forbes contributor, founder of the site Secret Agent Research, a creative content marketing trainer for small businesses and writes the blog, Generation Meh. Recently, she offered some interesting observations on an age-old truism that were picked up by the folks at Refinery 29: namely, Henderson questions whether the belief that “ALL publicity is good publicity” is actually true – particularly at a time when social media dramatically accelerates the rate at which publicity grows AND simultaneously leaves its originator (or target…) with substantially less ability to control the process.

I’d imagine most of us, for example, have mistakenly pressed “reply all” to an email – and while the results were hopefully not disastrous – they certainly have been for some (e.g., a certain ex-private equity dude in South Korea — and to think, that was all the way back in 2001…) And the “reply all” scenario is nothing compared to what can happen in today’s Twitter driven world – say, an offensive tweet sent by the (former) PR guru, Justine Sacco, during a flight to Africa that had already gotten her fired by the time she landed. You’d think someone that high up in the echelons of the PR industry might just be a little more careful… And that seemingly natural assumption is one very good reason why both incidents – and others of a similar nature - illustrate why Ms. Henderson’s thoughts on the subject are so worthy of contemplation.

To start, one thing is absolutely clear: we’re far beyond the age when only celebrities and politicians should be considering these issues. Today, both the opportunities and pitfalls of becoming instantaneous fodder for global commentary require little more than a smartphone. As an example of the “opportunity” side of the equation, Henderson cites the case of woman named Marina Schifrin:

On the other hand, of course, Henderson also points to other examples (more similar to those I noted) where one’s lack of forethought before pressing “send,” “reply all” or “post” can indeed prove disastrous. She concludes: “If you can skip . . . interpersonal unpleasantness and burnish your own personal brand in the process, well, professional etiquette’s loss is YouTube’s gain. It may be an emotionally stunted approach, but it’s an exceedingly socially savvy one.”

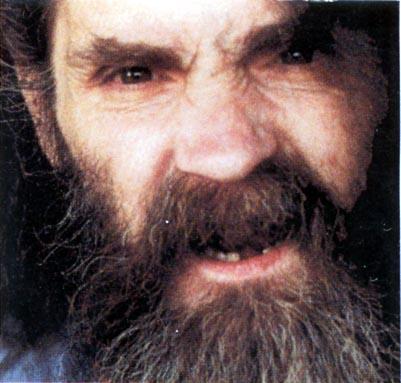

In general, I agree with Henderson’s basic analysis but believe we could benefit by further extending the discussion. Let’s get back to celebrities for a moment. In some sense, the definition of a celebrity is somebody who has achieved substantial positive publicity. Or is it… Angelina Jolie and George Clooney are rightfully called celebrities (and make vast sums of money as a result) based on a combination sexiness and talent. Chris Rock is a celebrity because he is funnier than almost anyone else who has ever lived. But, although everyone knows who Charles Manson is, would it be right ascribe that same word to a serial killer? Is North Korean leader Kim Jong Eun a “celebrity?” Anthony Weiner? Or how about that humiliated private equity guy? You might remember his story but I doubt you remember his name or would leap at the chance to hire him, right?

(Poorly thought-out personal branding . . .)

Hence, I think Henderson’s comment about the use of social media for personal promotion being “emotionally stunted,” is not entirely correct. The real point is that stupid (or, for that matter, downright evil) behavior absolutely won’t create the sort of publicity that leads either to direct monetization or to other forms “positive celebrity status.” Nevertheless, developing some type of intelligent individual branding is increasingly becoming an essential element for virtually everyone. And I don’t believe doing so is “emotionally stunted” at all. In an era, when one’s job can disappear in an instant and new opportunities can show up out of nowhere, being prepared with a personal PR plan (or at least some ability to shape one’s own image) is just common sense.

Professional athletes have always understood that protecting the name on the back of the jersey is just as important as protecting the name on the front. Perhaps because the concept is so integral to what they do out on the field, athletes recognize that successful monetization of image requires both offense and defense.

So, at the risk of minor hyperbole, we’re all celebrities now . . . It’s time to start thinking accordingly.

(well, maybe not EVERY athlete understands . . .)